Tularemia

Overview

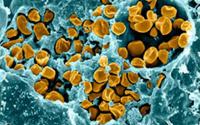

Tularemia is a rare but serious infection caused by the small, rod-shaped, nonmotile bacterium Francisella tularensis. The disease occurs throughout North American and Eurasia. In the United States, it is most prevalent in the western and south-central parts of the country, but cases have been reported in every state but Hawaii. Typically, only a few hundred cases of tularemia are reported in the U.S. every year.

The main animal hosts of F. tularensis are small mammals such as mice, squirrels, and rabbits. In humans, infection is usually contracted during the summer months and caused by bites from Dermacentor or Amblyomma ticks that have fed on these small animals or from contact with rabbit carcasses in winter. Other modes of transmission occur, including contact with contaminated water, air, or soil. Over the last half century, the incidence of tularemia has decreased in winter months and increased over the summer. Total incidence, however, has declined over this period.

There are several different types of tularemia, which vary in presentation and severity depending on the method of acquisition and the dose and virulence of the specific infecting organisms. Typically, tularemia is divided into six forms:

- Ulceroglandular tularemia is the most common form by far, comprising around three-fourths of all cases of tularemia. In ulceroglandular tularemia, the organism is acquired through the skin via arthropod bite or abrasion. Usually, the vector is a tick, but deer flies and mosquitoes can also transmit F. tularensis. A skin ulcer develops at the site of infection.

- Typhoidal tularemia (sometimes called septicemic tularemia) is the next most common type, at around 10-15% of cases, and is the most serious form. Pneumonia is a common feature. It is probably acquired by ingestion, although the precise mode of transmission is not completely clear.

- Pneumonic tularemia is uncommon, and is acquired by inhalation. Some patients with ulceroglandular and, more often, typhoidal tularemia will also develop pneumonia.

- Oculoglandular tularemia is rare and occurs when F. tularensis is introduced into the eye. This can occur from a splash of infected blood or perhaps when the eyes are rubbed after handling an infected animal carcass.

- Oropharyngeal tularemia is also rare and is caused by ingesting undercooked meat from an infected animal (almost always a rabbit).

- Glandular tularemia is also rare, and is clinically similar to the ulceroglandular form, except without the development of a skin ulcer. It is acquired through the skin, and may not require a scratch or abrasion.

Because F. tularensis can exist in aerosolized form and only 1 to 50 organisms are required to establish infection and cause disease, there is considerable concern that tularemia could be used as a bioweapon.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of tularemia usually develop within three or four days of inoculation, though in some cases it can take up to ten days for the disease to manifest. The organism is intracellular and spreads via the lymphatic system, multiplying within macrophages. Signs and symptoms, and the organs affected, vary widely depending on the method of inoculation.

- In ulceroglandular and glandular tularemia, common early signs are high fever, chills, swollen glands, headache and extreme fatigue. A skin ulcer develops at the infection site in the ulceroglandular form.

- Typhoidal tularemia is characterized by fever, exhaustion and weight loss. The lungs may become involved.

- Sore throat, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea are common in the oropharyngeal form of tularemia. Abdominal pain and intestinal ulcerations are common.

- Oculoglandular tularemia is marked by redness and pain in the eyes (conjunctivitis), often accompanied by a discharge. Swollen glands are also frequently seen.

- Finally, pneumonic tularemia causes a dry cough, respiratory difficulty and chest pain.

- Meningitis is an uncommon but potentially serious complication of tularemia.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of tularemia is based on the signs and symptoms described above, ideally combined with a history of recent arthropod bite or plausible environmental exposure to F. tularensis. The index of suspicion increases strongly with the presence of the characteristic ulcer.

Standard blood tests are not particularly helpful in diagnosing tularemia, although about half of all patients will exhibit non-specific abnormalities in liver function. Some patients develop elevated creatine kinase levels as a result of rhabdomyolosis; this is frequently associated with a poor prognosis.

A number of specific tests exist for tularemia, but they are not widely available. Direct examination of biopsy specimens or secretions by fluorescent antibody or Gram or histochemical stains is often helpful in diagnosis. F. tularensis can also be demonstrated microscopically with fluorescent-labeled antibodies. Antibodies are not typically present, however in the first ten days to so after exposure.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests can also be utilized.

F. tularensis can be grown in culture, although laboratory personnel are advised to take strong precautions before attempting to do so, as workers can themselves become infected. Ideally, patient samples should come from sputum or pharyngeal washings, as the organism is not present in large numbers in blood.